(Extremely Rachel Maddow voice): To understand why, we need to look at the 1957 Eldorado Brougham—and a man named Antoine.

At $340,000, the Celestiq isn’t competing with Tesla or Mercedes. It isn’t even trying to be part of the same conversation. It’s a rebuttal—to a century of decline, to a half-century of compromises.

For ten grand more, you can have a Rolls-Royce Ghost with its BMW-derived V12 and more leather and English pomp and circumstance than a battery-powered car could even dream of. But Cadillac has made audacious moves like this before. The original Seville was its answer to Mercedes. It was probably the best American car of its time—but it carried a stratospheric price tag: $14,267 in 1978 (in 2025: $67,000), when a Caprice cost $5,500 (in 2025: $26,000) and an S-Class 450SE rang in around $23,000 (in 2025: $114,000). The Eldorado of the late 1960s introduced front-wheel drive wrapped in Bill Mitchell’s finest proportions. And the 1957 Eldorado Brougham was, at the time, the most expensive American car ever built—priced at $13,074 (in 2025: $137,000)—and a better all-around car than the erstwhile monarch, the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud.

Cadillac’s upward arc grows steeper the further back you go. In the 1930s, its V12- and V16-powered models wore bodies by Fleetwood and Fisher that rivaled anything from Packard or Duesenberg—not cheaper alternatives, true equals.

The Celestiq is Cadillac going back to what it once did best: building something no one asked for, pricing it higher than anyone expected, and not caring whether anyone understood or even wanted it. Which is why the Celestiq matters more than its sales figures ever will. It’s not about volume. It’s about what it says: that Cadillac might finally remember how to be Cadillac again.

But to know whether that’s possible, we have to start at the beginning.

Let’s go back to 1701. That’s 256 years before the Eldorado. 201 years before the V16. A full century before Cadillac built its first car.

Back to a man named Antoine Laumet.

He was nobody—an provincial lawyer from Gascony who, as so many did on their arrival, reinvented himself in the French colonies. When he stepped off the boat in what is now Nova Scotia, he introduced himself as Antoine de la Mothe, sieur de Cadillac—a name he borrowed from a minor château near his hometown. He also invented a coat of arms, gave himself a fake noble lineage, and called himself a count. No one questioned it. He had confidence, a bit of land, and a royal seal.

In 1701, Cadillac founded a settlement on the straits between two great lakes. He called it Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit. Detroit.

That’s where this story begins. Because 200 years later, the name “Cadillac” would be chosen not for its technical accuracy, but for its myth—for the way it sounded. Because Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac wasn’t a general. He wasn’t a war hero. He wasn’t an engineer. He was a liar, a striver, a Frenchman with style and no particular honesty who showed up with nothing but a fake name and made it stick.

By the time Henry Leland needed a name for his new company in 1902, he didn’t want something mechanical or prosaic. He wanted something that sounded expensive: Cadillac.

That name now sits on a $340,000 hand-built electric flagship being assembled less than 30 miles from the site of the fort Antoine Cadillac founded. Because Cadillac—the brand, the machine, the myth—has spent the last hundred years becoming what its namesake always was: aspirational, invented, and just credible enough to get away with it.

But here’s the thing. Antoine Cadillac didn’t build anything himself. His success was persuasive. Cadillac the brand? It actually earned the title “Standard of the World.” With metal. With machines. With ideas. And then it gave that up.

Cadillac, the company, earned the title. It wasn’t a tagline. In 1908, the Royal Automobile Club of London awarded the Dewar Trophy to Cadillac for demonstrating precision manufacturing at a scale no one thought possible. Engines were disassembled, parts shuffled at random, reassembled, and fired without a hitch. That year, Cadillac proved it could mass-produce mechanical excellence. It became, without hyperbole, The Standard of the World.

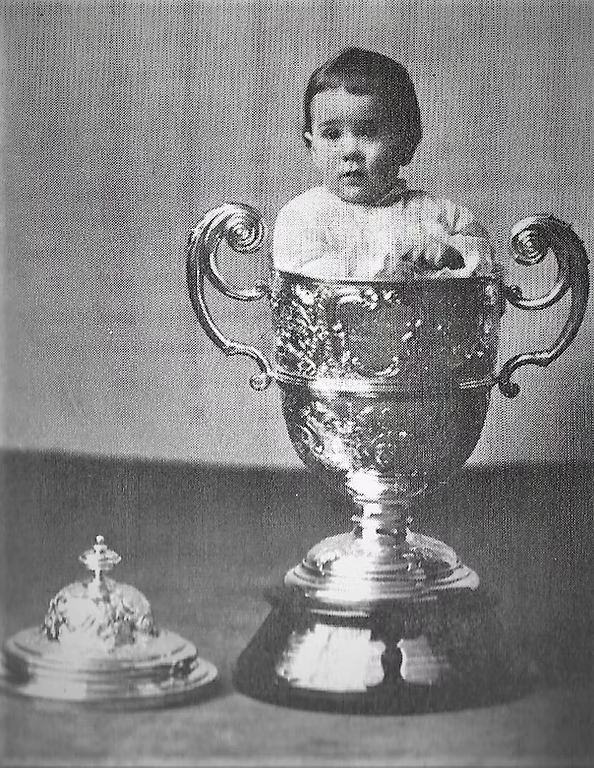

By the 1930s, it built the first V16 engine in an American car—not to win races, but to move weight smoothly, silently, and with authority. In 1957, it showed the world the Eldorado Brougham—a $13,074 (in 2025: $137,000) halo car that cost more than most houses and nearly as much as a Rolls-Royce. Four doors, no B-pillar, air suspension, perfume atomizer, electric everything. It was built at a loss. No one cared. It was a symbol.

For half a century, Cadillac was both the proof and the product of American luxury. By the 1960s, if you made it, you bought one. If you bought something else, it was because you wanted to signal rebellion—or because you couldn’t afford it.

And then the story changes. By the mid-1970s, Cadillac was still selling in volume, but innovation had flatlined. German and Japanese automakers were not trying to emulate Cadillac. Cadillac was trying to hold the line. The cars were bigger, the engines lazier, and the interiors less special. Downsizing came with the oil crisis. And with it, platform sharing. And with that, the Cimarron.

It had been more than forty years since Cadillac built its last V16. But the memory of it still lingered in the name. That’s what made the Cimarron so corrosive. It wasn’t just a bad car—it was a deliberate surrender. A Chevrolet Cavalier in Cadillac clothing, priced against a BMW 3 Series and aimed at buyers who couldn’t be fooled. It taught an entire generation to doubt the badge—not because of the product, but because of the intent behind it.

Cadillac’s post-Black Monday era through the dot-com bubble brought attempts at reinvention—the Allanté, the Northstar V8, the Art & Science design language, the Sigma platform—but nothing fully landed. The CTS-V came closest. The XLR tried. The STS lost. The Catera forgot what it was supposed to be. Cadillac was no longer the car you bought to show you’d made it. It was the car you leased because it had good incentives.

Even when Cadillac made a good car, the follow-through was inconsistent. No second acts. No long-term vision. Every success felt like a lucky break. Every concept like a promise that would never be kept. The engineering team never forgot how to build a world-class car. The rest of the organization forgot why they should.

Cadillac captured world leadership in the early 20th century with its award-winning engineering and designs, held onto it with a silken V16 in 1930 and the iconic Eldorado Brougham in 1957, but squandered that prestige through hurried downsizing and brand-diluting badge engineering in the 1970s and 1980s. It is now staging a two-pronged return built on ferocious V-Series halo cars and rapid electric-vehicle expansion. Its 500-cu in. V8 of 1970, with its stratospheric 550 lb-ft of torque, remains one of the highest-torque engines ever sold in an American luxury car—yet that same displacement became a liability when fuel shocks and emissions rules hit.

Today, the CT5-V Blackwing, the 682-hp Escalade-V, the strong-selling Lyriq, and the bespoke Celestiq collectively demonstrate that Cadillac can once again combine technical daring with genuine desirability. Whether that eclectic portfolio will cohere into a durable “Standard of the World” depends on Cadillac’s ability to sustain engineering excellence, resist volume-driven cost-cutting, and deliver consistent luxury experiences across both combustion and Ultium platforms.

Thanks, Rachel. Let’s review Cadillac’s hits and misses over its 123-year history and determine how it can keep up the momentum to regain its previous position at the top of American luxury.

I. The Standard of the World

Cadillac Motor Car Company formally opened in Detroit on August 22, 1902, reorganized with its new name from the reorganized remains of Henry Ford’s second failed venture, the Henry Ford Company (his third venture—the Ford Motor Company—stuck). Henry Leland named the firm after Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, the French officer who founded the city two centuries earlier, and insisted that every component be machined to gauge rather than hand-fitted. That commitment paid spectacular dividends at Brooklands in March 1908 when Royal Automobile Club judges disassembled three Model K Cadillacs, mixed their 721 parts, added 99 new service pieces, and reassembled all three cars without filing or reboring a single item. Each car then lapped the circuit flawlessly. The Dewar Trophy they awarded was the first ever earned by an American manufacturer, cementing Cadillac’s reputation for scientific production.

William C. Durant’s General Motors paid $4.5 million (in 2025: $172 million) for Cadillac on July 29, 1909, keeping Leland and his son Wilfred at the helm. Within three years, Charles Kettering’s Delco division had supplied a compact electric motor powerful enough to spin a cold engine briefly without burning out. The Model 30 thus became the first car one could start from the driver’s seat, a safety breakthrough that earned Cadillac its second Dewar Trophy. Closed bodies, full electrical lighting, and a simplified sliding-gear transmission quickly followed, reinforcing the marque’s leadership.

September 1914 brought a true engineering bombshell: the Type 51 V8. Designed under Scottish engineer D’Orsay McCall White, the 314-cu in. L-head produced 70 hp—double the output of Cadillac’s retiring four-cylinder—and propelled factory-bodied cars to 65 mph on the rough American roads of the day. Competitors capitulated: Packard rushed to market with its Twin Six, and Pierce-Arrow abandoned its sixes for a twelve. Cadillac, meanwhile, refined the V8 with a cross-plane crank in 1923 and synchromesh gears in 1928, keeping its luxury crown through the prosperous twenties.