Once dismissed as old-fashioned, tactile switches and knobs are being celebrated again for their practicality and for keeping drivers safer. Studies show how dangerous touch-only interfaces can be, and those vast screens were often less design than accounting, a cost-cutting move disguised as luxury. Automakers from Volkswagen to Ferrari are retreating, regulators are pressing back, and buttons are returning to the driver’s seat.

Cutting Costs Disguised as Luxury

The industry fell in love with glass when Tesla’s Model S arrived stripped of switches and fronted by a 17-inch tablet. Others soon followed, fitting oversized screens to everything from hatchbacks to SUVs. The pitch was seductive: cars as smartphones, cabins reduced to minimalist geometry, a look sold as modern luxury. Screen size itself became the measure of prestige. In truth, replacing dozens of knobs with one display saved millions. Insiders admitted the boom was “an opportunity to cut costs” dressed up as futurism, a sleight of hand exposed on the road as anything but.

Mercedes-Benz design chief Gorden Wagener admitted that giant panels are “not luxury,” adding that “we have to create luxury beyond the screen.” Mercedes’ EQS carries the largest display on the road, a 56-inch monstrosity dubbed, seriously, the “Hyperscreen.” The contradiction makes the critique sharper: real luxury comes from craftsmanship, not from a wall of glass dulled by fingerprints and destined for obsolescence when the software expires.

Distracted Driving

Beyond style or cost, touchscreens reveal a harsher truth: they make driving more dangerous. Buttons and knobs can be found by feel, but glass demands your eyes, and the data proves it. AAA measured infotainment use at an average of 40 seconds with eyes off the road, enough at 25 mph to cover nearly five football fields. A Swedish test underscored the point when a 2005 Volvo with physical controls completed routine tasks in 10 seconds and 306 meters, while a modern SUV needed 44.6 seconds and nearly a mile. Even BMW’s iX took three times as long as the old Volvo. The verdict is obvious: tactile controls keep attention on the road, touchscreens drag it away.

Pushing Back

Regulators and watchdogs are circling. Euro NCAP has already drawn a line in the sand: from 2026, no five-star rating without physical switches for the horn, wipers, signals, hazards, and SOS. It called out the industry-wide habit of burying basic functions in menus, warning that forcing drivers to look away from the road is indefensible. U.S. agencies have been slower, but NHTSA has signaled distraction will not escape future ratings. Automakers will go on selling glass dashboards as progress until the practice is checked by force. In the 1970s, the mere threat of a convertible ban froze development cold. The same fear should hang over the touchscreen dashboard.

Buttoning Down

Some automakers are reversing course even without pressure. Euro NCAP has no regulatory teeth, only reputation, but that alone has pushed a few brands to abandon touch-only interfaces and restore real buttons. The change is most visible on steering wheels once cluttered with haptic pads, now restored with switches drivers can find by feel. A few years ago this retreat seemed unlikely, but feedback was blunt: what manufacturers sold as progress was always a nightmare.

Ferrari learned fast that haptic controls were a mistake. The SF90 Stradale launched in 2019 with touch-sensitive pads on the wheel, but customers revolted, and commercial chief Enrico Galliera admitted the design broke the basic rule of eyes on the road, hands on the wheel. The upcoming Amalfi restores physical switches, including the red start button, and Maranello will retrofit the wheel to earlier cars while promising every future model will “rebalance the ratio” toward tactile controls.

Volkswagen made one of the most visible reversals. In 2019, it stripped buttons from models like the Golf and ID.3, replacing them with capacitive sliders and haptic pads. Drivers hated them, and by 2023 new CEO Thomas Schäfer admitted the experiment “did a lot of damage” to VW’s reputation. Design chief Andreas Mindt promised the fix: every new model after the ID.2all will restore physical buttons for essentials like volume and climate, with real feedback instead of guesswork. The shift mirrors Ferrari’s retreat from haptic wheels, but where Maranello is retroactive, Wolfsburg is only prospective.

BMW embraced large displays, but it never abandoned physical redundancy. The new 7 Series stretches glass across the dash, yet CEO Oliver Zipse has defended the rotary controller and other real buttons as essential. He argued that customers want haptic feedback and that all-screen interfaces compromise safety. His verdict was blunt: “We will not go all-screen.” For Munich, tactility is not nostalgia but insurance against distraction and obsolescence.

Recent moves by Lexus acknowledge that the problem runs deeper than touchscreens. Its widely criticized trackpad forced drivers to swipe through menus for basic tasks, a distraction even without glass. Before becoming Toyota’s CEO, Koji Sato admitted the system was a mistake and confirmed that newer models such as the IS and NX would restore buttons for essentials. It was a concession that even Japan’s designers had to walk back the infotainment experiment.

Volvo set the template for touchscreen minimalism with the 2015 XC90, which buried nearly every function in its Sensus system. Praised for clean design, it soon became a case study in how not to build an interface. A decade later the EX90 is still dominated by a portrait display, with only the basics spared, and the hardware controls otherwise unchanged. The rhetoric, however, has shifted: Volvo now concedes the minimalism went too far, even while selling the same screen-heavy interior. From Scandinavia’s design darlings, that half-step is telling.

The backlash is now driven by customers and amplified by common sense. Drivers and reviewers have grown vocal about their dislike of convoluted interfaces for basic tasks, and social media brims with ridicule of multi-step procedures that a knob once solved in a click. A Reddit thread titled “Touchscreens in cars are incredibly stupid and actually quite dangerous” drew thousands of upvotes, a blunt gauge of sentiment. Automakers have noticed. After years of stripping cabins bare, they are repopulating dashboards with real buttons and switches. It is not nostalgia, but recognition that customers never accepted cars as disposable gadgets.

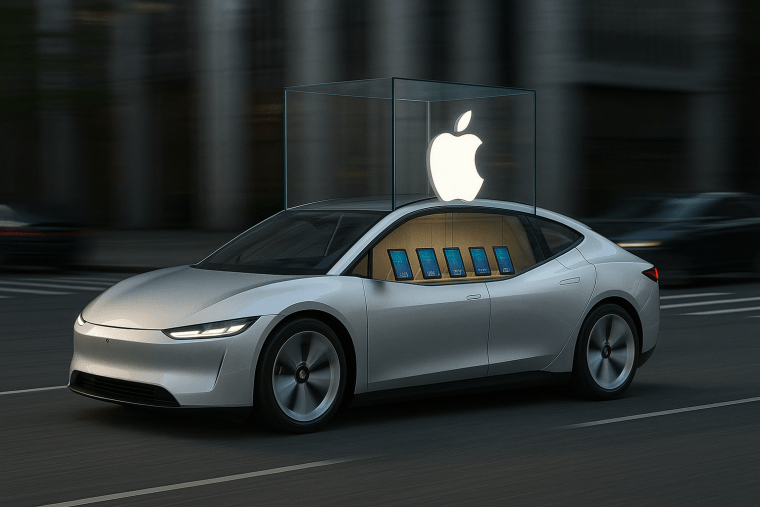

Rejecting the Apple Store on Wheels

The resurgence of physical controls is not just about safety or nostalgia, it is about rethinking luxury. For years designers staged cabins to look like Apple Stores, mistaking screens for progress. Many drivers never bought into that premise. True luxury is an interface that works intuitively: the sculpted knob your hand finds without a glance, the toggle that clicks with precision, the button that responds instantly. BMW introduced tech as luxury with the 750iL’s optional fax machine and integrated car phone, and the idea stuck. But in the march from gadgets to glass walls, the premise went too far.

Tactile controls reconnect the driver to the machine, turning simple actions into rituals: a switch flicked to change modes, a red start button pressed with ceremony. Compared with swiping through menus, it is the difference between commanding a car and configuring a laptop. A good interior lets you forget the interface, your hand finding the right control by instinct. That simplicity is what automakers are rediscovering as they bring back buttons and dials.

In Praise of the Physical Button

The button’s return is not nostalgia, it is necessity. A car should not be reduced to a touchscreen on wheels. Driving is an act of control, not a software exercise. The satisfying click of a switch and the certainty of a knob found by feel are what keep driving alive. The button is back because it belongs, and its comeback shows that progress in cars is measured by clarity and control, not by glass.

-eᴍ